Life pre-Grindr? Yes, there was such a time. In fact, most of time has been that way, but guys being into guys is certainly nothing new. Sure, there’s the “old-fashioned way” of meeting a guy in a bar, but that is actually hardly old-fashioned. The first gay bars didn’t exist until about 100 years ago, so what about before then? LGBTQ history is a fabulously rich and diverse subject full of heroes and tragedies and love, but what about the nitty gritty of just how did guys find each other in past centuries?

The way we dressed

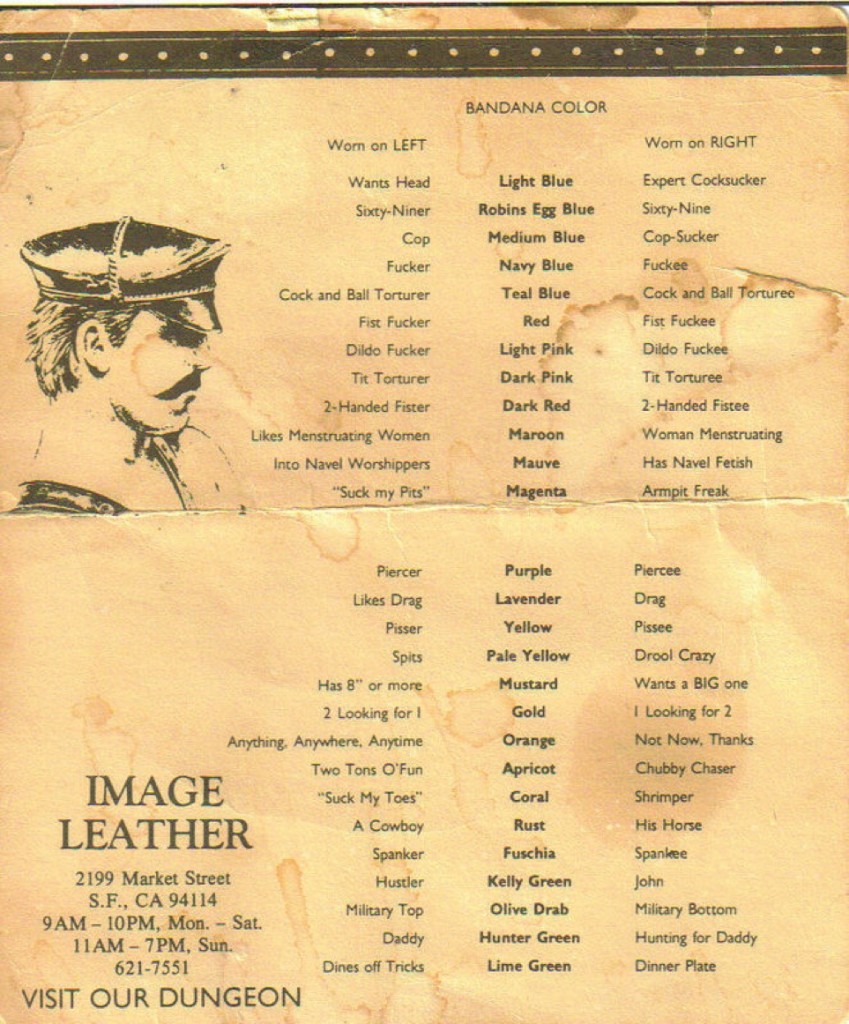

Ever heard of “the hanky code” (or maybe used it)? Especially in the late 1960s to 1980s U.S., tucking a certain color of bandana into your back pocket was a signal for preferred sexual practices. Scholars disagree on the origins of the hanky code, citing possibilities such as Gold Rush California, Weimar Berlin, 1970s New York City, and the World War II U.S. military. Many argue that it gained popularity in New York City during the 1970s because of a Village Voice article that (sarcastically) suggested guys needed a better way of signaling their desires than just wearing one’s keys in a particular rear pocket (the right back pocket meant that the guy was a “bottom,” while the left back pocket meant he was a “top.” That article laid out the first few handkerchief colors, but the list grew over time. On the right there is a 1970s version of the list (via reddit) that you can click to expand.

A gay historian in Cologne, Germany told me that it was sometimes the certain way a man would wear his hat and that there was a “dress code” for finding each other (he talks about it at 1:40 of this video).

Judy Grahn in Another Mother Tongue talks about her informal survey of 500 people to see if they had also experienced what she had in high school in the U.S. — that wearing green on Thursdays meant you were queer. About half of those surveyed said they recalled something similar.

In more modern times, as male-male love was increasingly decriminalized, more overt “tells” like these T-shirts could be worn. Some customs like a single ear piercing have also been very popular in the Western world.

In a lot of cultures it was unnecessary because guys were expected or encouraged to fool around with each other.

Yup, a dream world did exist. Every time and place has had its own understanding of sexual identity and sexual practices. Today we use labels like bi, straight, and gay, but many other cultures have had (or still have) other constructions. A number of indigenous cultures in the South Pacific, Africa, and South America, included what modern scholars call “ritual homosexuality.” For example, we have accounts from European anthropologists describing men in multiple countries having sex with each other as part of a masculinity ritual or as a regular practice.

Specific places

There have always been certain places that we gravitate to to find each other. The free Quist app has a map of places that we know used to be cruising grounds all over the world like the underground public toilets of Trubnaia Sqaure in Moscow, the city’s busiest cruising ground of the 1930s. One man accused of the crime of sodomy in 1941 claimed he had once been touched sexually against his will there but “did not object,” and then returned weeks later, according to court documents, “with the deliberate intention of committing sodomy [and] in this manner…committed acts of sodomy about five or six times.”

Between 1850 and 1860, the Champs-Élysées and the surrounding area were the principal gay cruising grounds of Paris. An 1888 account of the “Tree of Love,” located near the Café des Ambassadeurs, described it as a “headquarters” of men seeking men: “Every evening around this tree, one can see vile rascals wandering about, easily recognizable by their clean-shaven face, their lifeless gaze and especially the peculiar way they sway their hips as they glide rather than walk over the ground.” It’s called a sashay, thank you very much!

Besides “the look,” queer men looking for each other could try to identify each other by the way they walked or by other mannerisms, or could learn by word-of-mouth where to meet up with each other, not unlike today. It only took one time to stumble across a certain train station or park and get cruised to know to go back there again. (One of the reasons that learning LGBT history is so cool is because, if you go on a LGBT history walking tour of a city, it usually points out all of the spaces where gay bars or crusing spots used to be.)

Secret language

We still have our own lingo today, which includes words that we have redefined to mean something other than their common definition (i.e., top, drag, twink, otter, camp), but even before these became terms we used to identify ourselves in an online Grindr profile, they were meaningful code used in real life. There was actually a gay language, Polari. Here’s a list of some Polari words and their translations into modern English. There was actually a short film made this year in that language:

Today many of our terms like “drag queen” have gone completely mainstream and now their meaning is known to non-LGBTQ people, but decades ago these terms were our own secret slang. There have been several gay-to-straight dictionaries written, including Fantabulosa (2004) and the 1972 The Queen’s Vernacular.

Symbols

A bar or individual trying to maintain safety but still indicate they were into dude-on-dude action could use certain symbols to draw the attention of those in the know. Many places today continue to fly the rainbow flag, which first flew in San Francisco in 1978, as well as other flags like those associated with the leather community, to show that they are gay or gay-friendly. People wear pins or use bumper stickers with the pink triangle, an equality sign, or the rainbow to indicate their sexuality. And many gay businesses have names which are subtle nods to gay culture, such as “Giovanni’s Room” (a bookstore in Philadelphia).

Pansies and certain other flowers have been associated with us for centuries. Oscar Wilde popularized the use of a green carnation as a symbol for one’s sexuality. He and his supporters would wear one in the lapel of their shirt or jacket.

Want to learn more about queer history? Download the free Quist app for a daily dose.